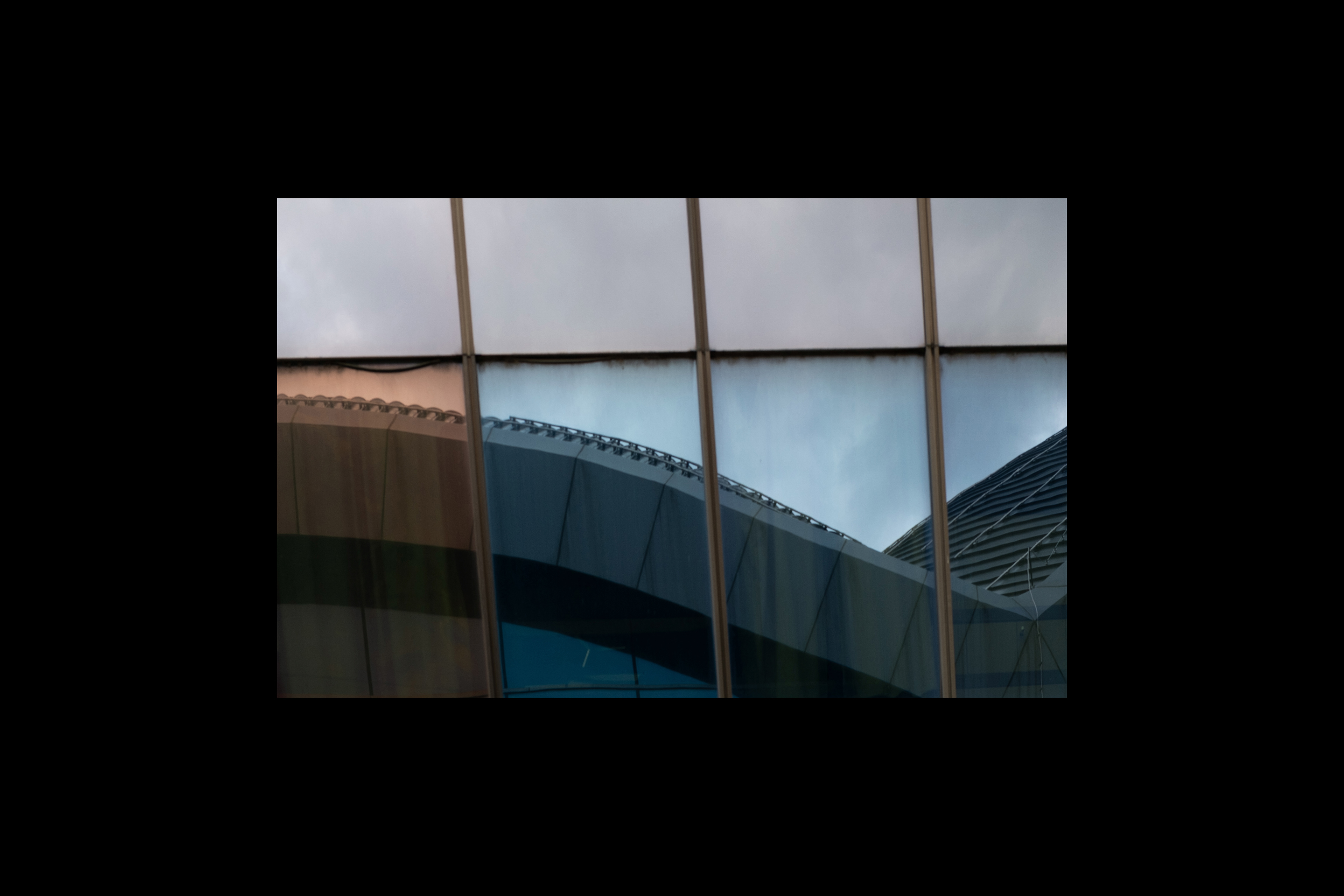

A Fake city. Statues and new buildings. Empire style made of mirrored glass. Architectural kitsch.

The epigraph of this essay is formed by the headlines of numerous press articles on the topic of the "Skopje 2014" plan, and my new photo project is a conceptual exploration of the controversial architectural heritage of Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia. So, the "Skopje 2014" plan – what was it? Ugliness, a visual catastrophe, or a kind of architectural theater that brought the city recognizability? A political utopia or a unique cultural phenomenon that still awaits interpretation? In any case, I find it all mesmerizing! Let's take a look!

Skopje 2014 vs. Skopje 1963

Walking past the Post Office building in Skopje, I notice the colorful facade, the cracked pavement, and patches of grass in the fissures of the concrete structure built in 1974. A few hundred meters away, across the Vardar River, stands the large white building of the Archaeological Museum, constructed under the “Skopje 2014” project, during which the city acquired a new image. Such is the urban paradigm of today’s Skopje. These two city structures are unstable and held together like water in the palms of one’s hands, but it is precisely their atypicality that gives the city its special uniqueness.

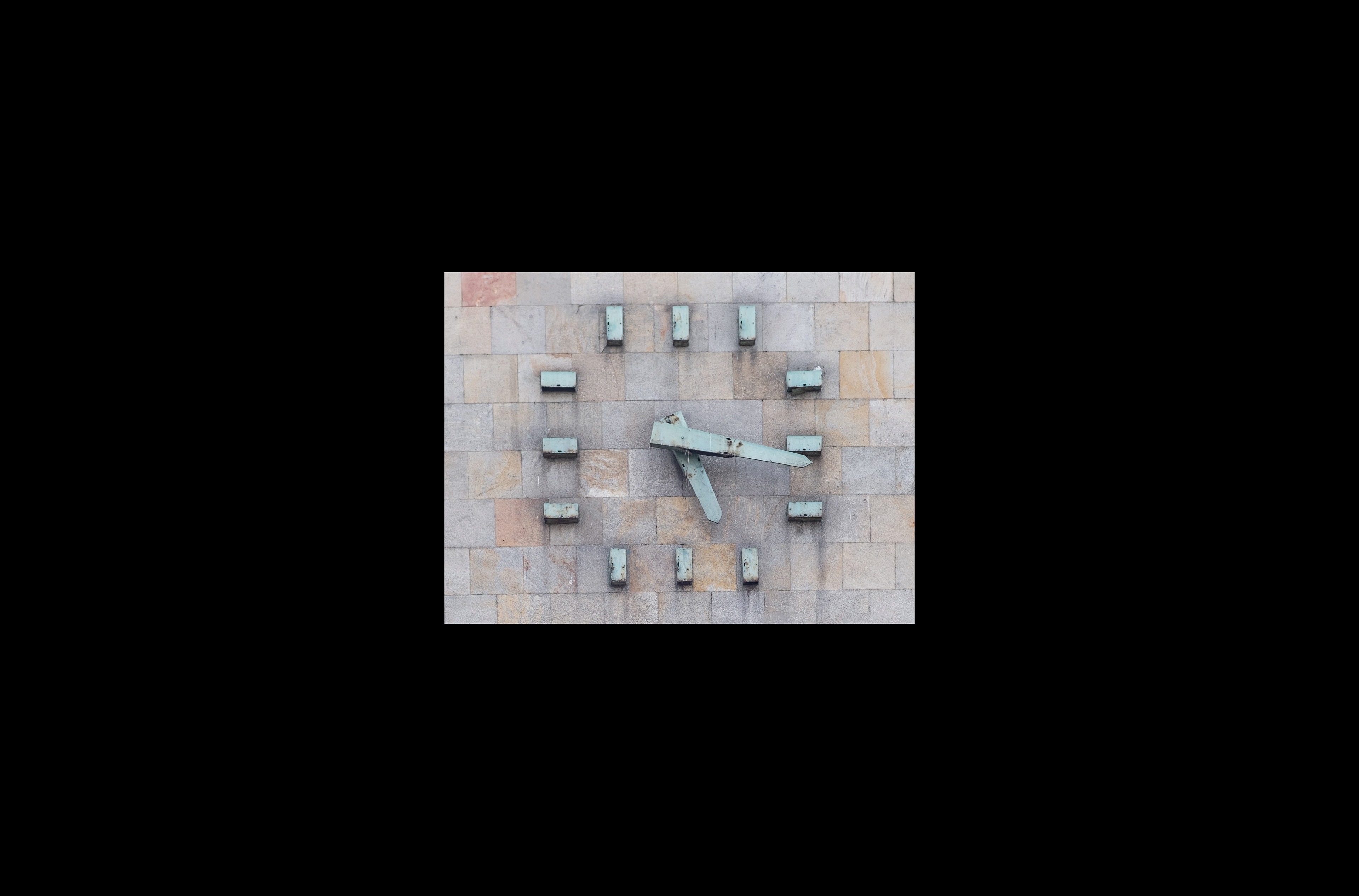

The clock at the Main Railway Station stopped at 5:17 AM, the moment when, on July 26, 1963, the most destructive earthquake in the city's recent history struck Skopje. This natural disaster changed the entire face of the city, located on the Vardar River.

The first in a series of quakes lasted 20 seconds, followed by several more.

The first was also the strongest – it caused almost all the damage and was the most devastating for Skopje.

Skopje is destroyed, and the bad news is true.

"I walked through the entire center, which at the time wasn’t very big, and there was plenty to see. Ruins were everywhere, people were buried under the rubble – it was a state of complete shock".

The tragedy led to a full reconstruction of the city. In 1964, the United Nations and the Yugoslav government announced an international competition to rebuild central Skopje. First place, with numerous reservations and limitations, went to architect Kenzo Tange, known for his landmark project of the Hiroshima Master Plan in Japan. Tange’s concept for Skopje was criticized as utopian and overly idealistic. In the end, the architect and his team proposed a project that was implemented – though only partially and with significant alterations. The final design of the city represented a composition of existing and brutalist architecture, expressing many of the modernist creative ideas of its time.

Disneyland in Skopje today. Reality or fiction?

More than 10 years ago, a large-scale reconstruction plan in the capital of North Macedonia sparked wide public reaction.

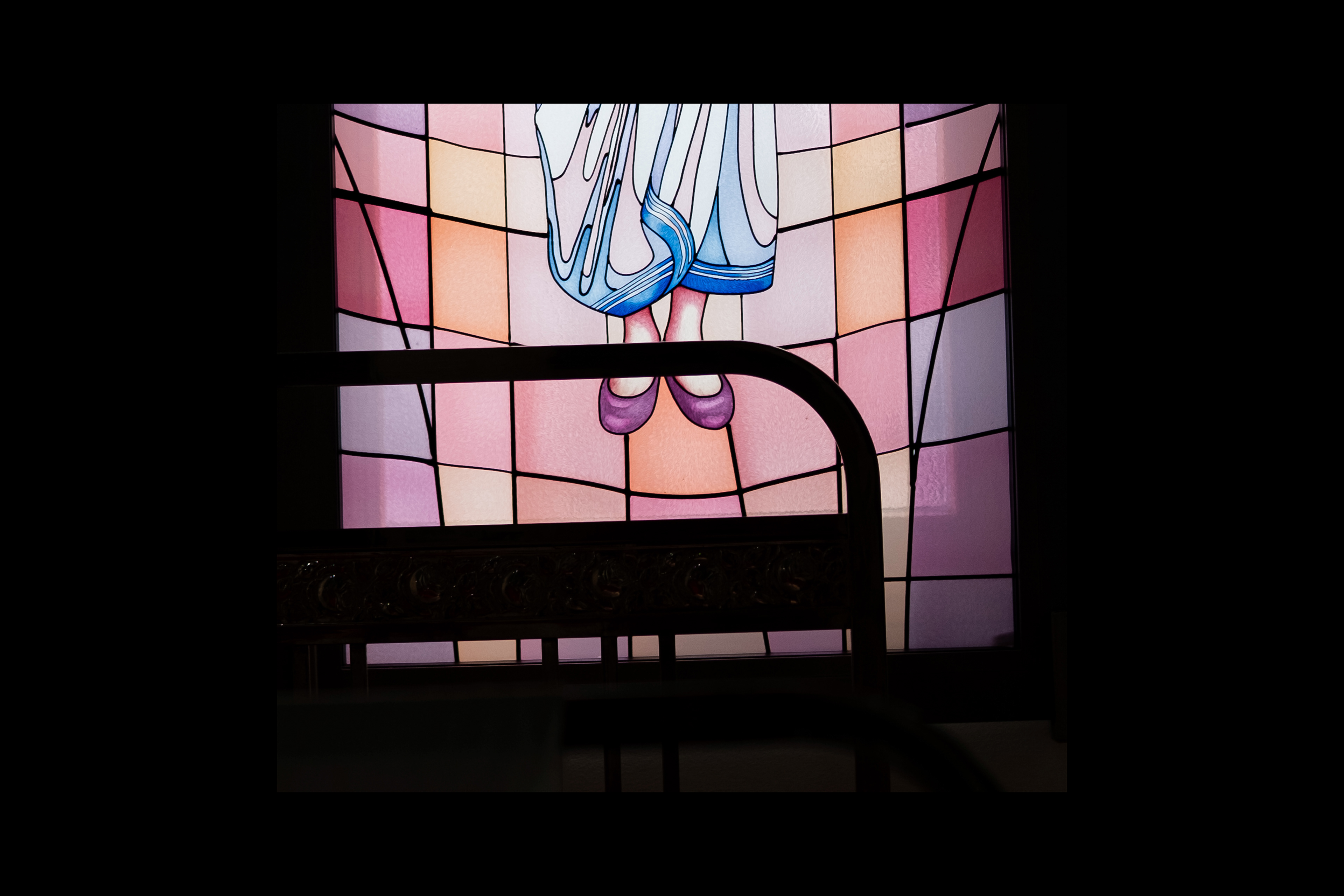

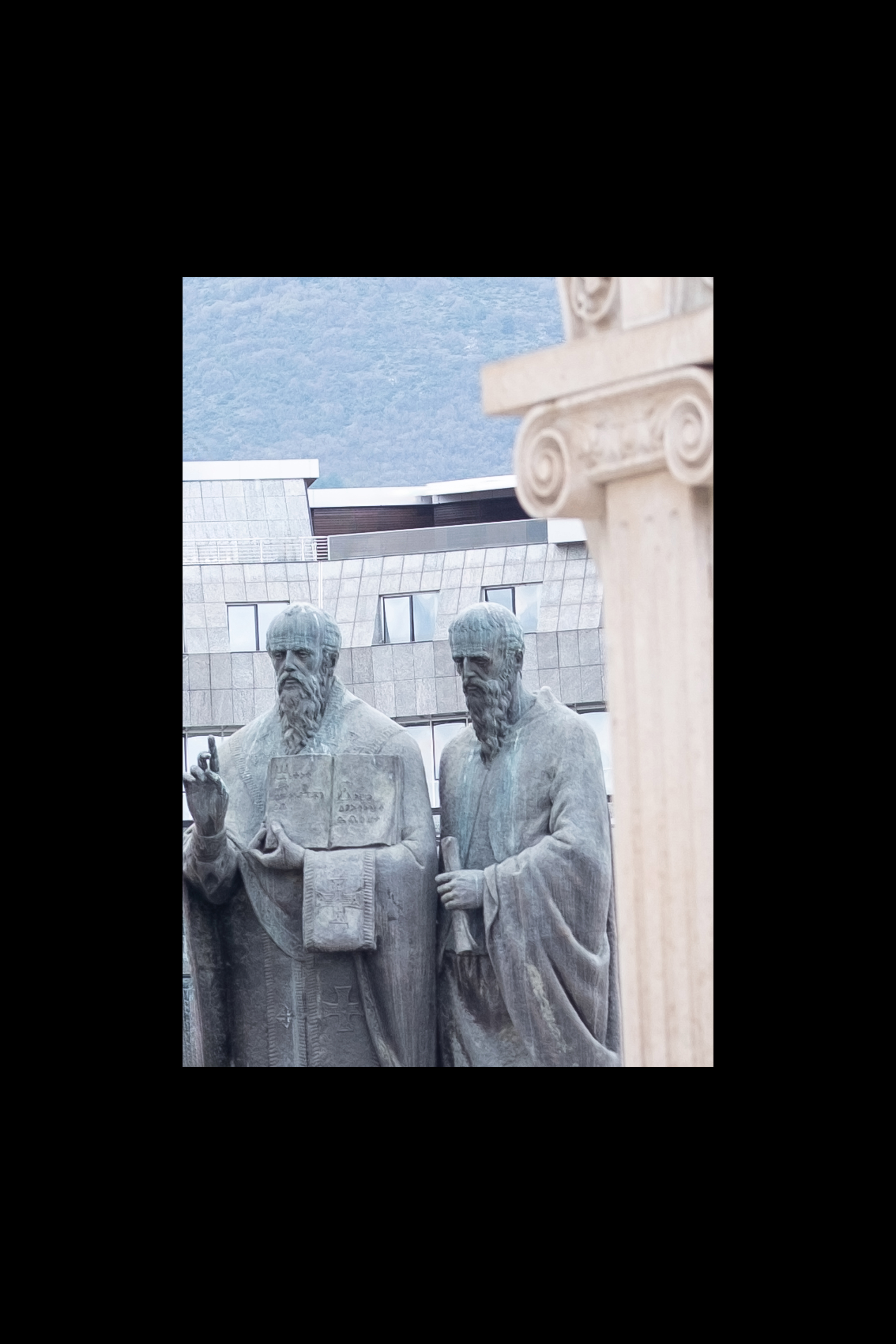

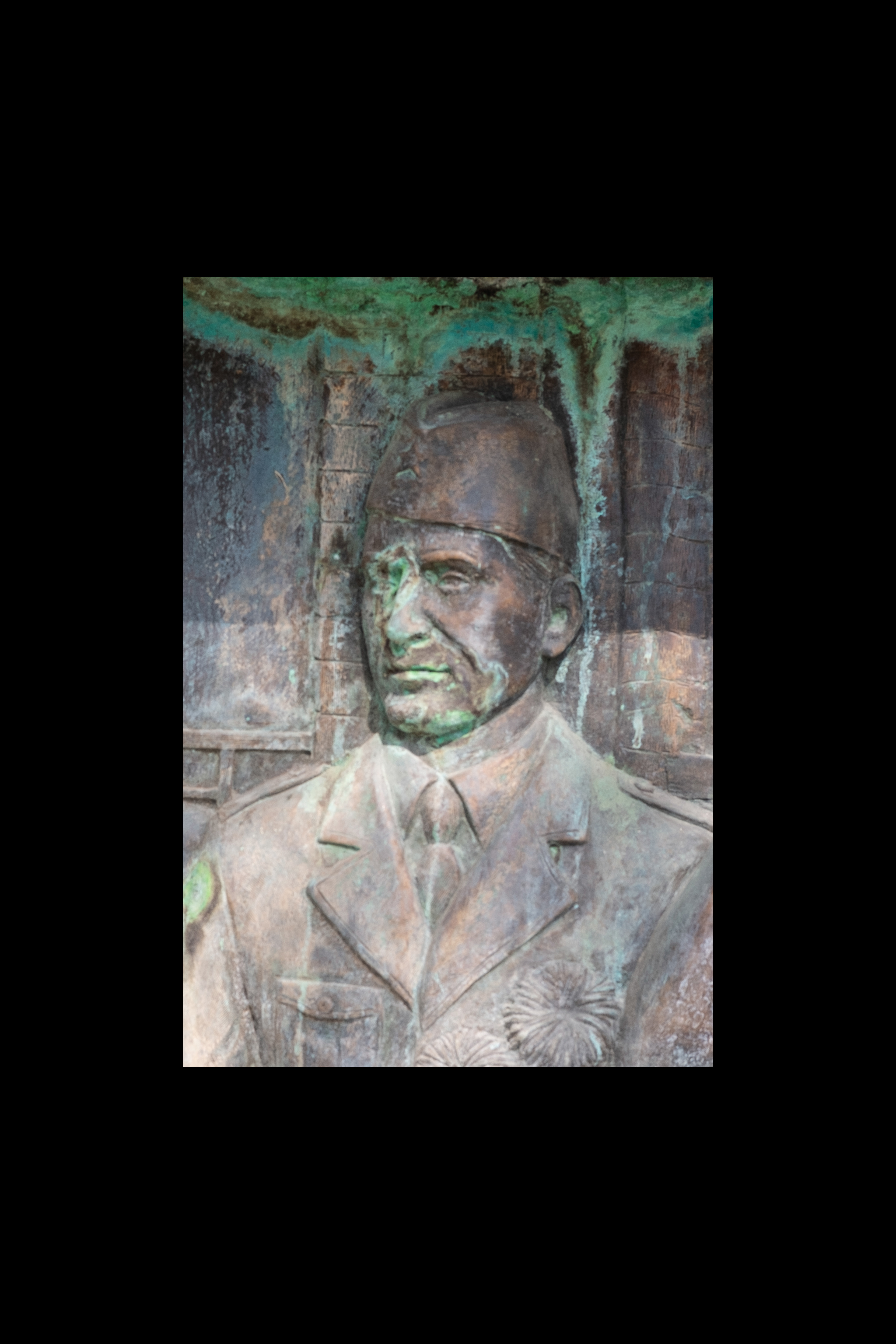

Under the banner of “Skopje 2014,” numerous statues, monuments, and neoclassical and baroque architecture appeared throughout the city. The stated goal of this project was to attract international investment and develop tourism in Skopje. But, as usual, opinions were divided.

"At first, people were skeptical, but now they see that this place is truly wonderful for both the residents of Skopje and travelers".

That’s what some believed. While others questioned the tastefulness of the classical antique buildings and bronze statues.

International coverage at the time didn’t avoid the tired comparisons to Las Vegas and declared that "Skopje 2014" was not a master plan or a cohesive whole, but rather a collection of monuments, buildings, and facades. And that was, generally speaking, hard to argue with.

As stated, the aim of the project was to attract investment and tourists, but it became a source of alienation for the local population, who were never the primary concern of the large-scale reconstruction, completely detached from their everyday lives:

"Where my friends used to fish in the river is now a place for selfies, and where they once sat in the shade of trees, now stands a monument to a distant ancestor in the midday sun".

"Statues sprout from the ground overnight as trees are cut down. A giant monument dedicated to Mother Teresa is planned. The riverbanks seem to sag under the weight of too many buildings, and in the river – too shallow to swim – there are ships. Imagine how the older generations of Skopje feel, when even I am just a foreigner in my own hometown".

These are just some of the comments from a major article on the topic by Rachel Ling on the website Failed Architecture.

Many at the time agreed that the plan was tasteless and a complete farce, but what effect does Skopje’s postmodern transformation have on its residents today?

"A third man, whose English was limited, said just one word: "Disneyland".

That’s how that article ends, sharply. And for me, it was very interesting to dive into this fairy tale today.

Skopje. My main thoughts from being in and photographing the city.

• The "Skopje 2014" plan. I can’t quite say I dislike it.

• You definitely need courage to make a city like this. Even borderline courage. To admit to everyone and say: we can’t do it any other way, but this way we can. And truly, it works. In its own way, of course. But this – this is the best thing for identity!

• Someone high up in Skopje’s government absolutely hates modernism, brutalism, and any kind of constructivism. Truly hates it. Physically. To such an extent that buildings of modernist heritage from the 60s and 70s are being massively redone. Facades are stripped and everything is fanatically redone in classicist and baroque styles. Naturally, it turns out “as we are able.” But the mass scale of this phenomenon gives rise to its uniqueness.

• There are a lot of sculptures. I mean a lot. Literally hundreds! Everywhere!

Am I telling any kind of story with my project? Not really, or maybe several at once: sketches, visual essays, images that, intertwining, give birth to unspoken texts of other stories, still unconscious, only just outlined.

So, in Skopje’s recent history there are two extremely interesting (and also terrifying, unthinkable, and paradoxical) turning points that left an indelible urban mark: 1963, when a devastating earthquake destroyed 80% of the city’s buildings, and 2014, when a decisive blow was dealt to Kenzo Tange and other modernist experimenters, wrenching the ancient Macedonian-Ottoman city from the grip of architectural oblivion. Spoiler: burying Tange under an avalanche of didactic statues of dubious artistic merit, straight out of a propagandistic history textbook, didn’t quite succeed – but as a cultural phenomenon, all this is astonishing. In the end, the plan worked, revealing to the world a new architectural reality: a controversial, distinctive, vibrant, and living city, the likes of which are hard to find on the contemporary map of Europe.